A couple of months ago, I took ‘the hardest exam in the world’ – at least partly of my own volition. Masochistic, I know.

I say partly, because I was cajoled into taking it by my former professors: they, eager to see one of their students succeed at the test, and I, desperate, as ever, to impress them.

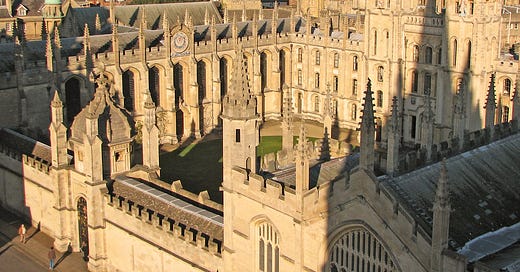

The entrance exam for All Souls College, Oxford attracts over 150 applicants every year, the vast majority of whom will have been awarded high firsts in their undergraduate degrees at the university. Typically, just two of them – and sometimes, according to the college, none – are awarded places as All Souls ‘fellows’.

To the disappointment of my professors, I did not become an All Souls fellow – which, I’m sure, after you discover how I answered the exam questions, won’t surprise you. But the benefits for successful applicants are enviable: an All Souls fellow gets a free room in the college, fully-funded tuition, and an annual stipend for seven years. If that wasn’t enough, I hear they also get to attend some very fancy dinners.

You might have come across articles with headlines like mine, which publish questions from the All Souls exam, but I’ve seen few accounts from people who’ve actually done it, so I thought I would share my experience and how I answered the questions.

Before we get into that though, some history!

The All Souls exam is, in keeping with the theme of this Substack, an anachronistic institution: quaint and ritualistic, it feels – like many things in Oxford – as though it belongs to another time.

All Souls College was founded in 1438 to commemorate victims of the Hundred Years’ War (its full name is College of the Souls of All the Faithful Departed). The entrance exam has been around since 1878, though it’s only been open to women since 1979.

In the past, one paper saw examinees receive a card with a single word on it, about which they were then expected to write coherently for three hours. Mercifully, they dropped that part in 2010.

Now, the examination is comprised of four three-hour papers, which are taken over the course of two days: two papers in your specialist subject (most likely the one you have a degree in, so, in my case, history), and another two – extremely daunting – ‘general’ papers.

I woke up at 5:40 to catch the 7am train from London to Oxford. The women’s dress code for the exam was the ‘equivalent attire’ to a suit and tie, and academic gowns were mandatory. In the absence of alternatives, I reluctantly put on my old school uniform – a scratchy white blouse and a pair of shapeless black trousers – and stuffed my gown – still faintly stained from post-finals festivities – into my rucksack.

At Paddington Station, I saw a girl who had already donned a well-ironed gown and did my best not to make eye contact. Once we reached Oxford, the people in gowns multiplied and, sleepily, I followed their trail to the examination centre in the north of the city.

Once we reached the exam hall, about half my fellow examinees pulled out detailed notes, which they began studying intensely, while the rest started loud conversations about their latest research projects. I was left awkwardly between the two groups, unsure of what to do with myself.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m far from above these bookish tendencies. Usually, I’d have been among those immersed in fervid note-reading until the very last minute. But I’d been told by my professors that there was no point in revising for the All Souls exam, and that, in preparation, I should read exclusively to improve my style. I was advised not to revise the content of my courses and instructed, instead, to read the LRB (‘if it didn’t bore me too much’), The Spectator (‘avoid the culture wars invectives’), and some Orwell and Trevor-Roper, as well as, vaguely, to ‘ponder things like the rehanging of the National Portrait Gallery’.

In the midst of jobs applications, I hadn’t got round to revising, reading for style or much ‘pondering’, and unlike the examinees who’d already started their Master’s degrees, I didn’t have any research to monologue about. So I sat alone, stopping briefly to chat to my friend Antonio – a charming and eccentric international student from Northern Italy, who, as a teenager, used to paint model army miniatures, and now dresses in beautifully-made ties and waistcoats.

Once Antonio had moved on to speak to his fellow Master’s students, I checked my phone so I could look as though I was reading something. There, I found an enigmatic email from one of my professors:

‘Don’t shoot until you see the whites of their eyes.

G.’

*Stay tuned for pt. 2 to read about the unhinged questions that were set and how I answered them…*